When I got the call from my friend Cheryl Pawelski at Omnivore Recordings to do the audio restoration and mastering for recently discovered Hank Williams recordings, I couldn't believe what I was hearing. I mean, really, how cool is this? Unreleased Hank Williams?! Cheryl said that the recordings were in pretty rough shape, but like so much of the work that I do, they are the only known copies in existence, so I worked with what I had and made the best of it. The recordings, all taken from 16" transcription records, had already been transferred and digitized, and were sent to me the next day. They were indeed pretty rough.

I knew it could sound better than this. I've worked with a lot of similar transcription discs over the years, and if played with the right stylus, they can end up sounding as good as a master tape.

One of the original 16" records

I did what I could with the versions I was given and sent those over for review. It was an improvement, but still not great. After talking it over with compilation producers Cheryl Pawelski and Colin Escott, we decided to try new transfers. I called George Gimarc, the owner of the original transcription discs, to see if he was comfortable with sending them to me. No problem; he agreed and I had the originals in my hands a couple of days later. Now I could really work from scratch.

I cleaned the records thoroughly with a record vacuum and picked a stylus that I thought might be a good fit. This is how my first transfer sounded:

Yes! This was good. You may think it still sounds noisy, but I heard potential. This is what I heard under all that noise:

I also noticed that my transfer sounded slower than the original version I received. Did the turntable used for the original transfer play a little too fast? How could I be sure? There's a cool little trick I can do with something that is usually an annoyance: ground hum. In North America, if there is a ground hum present on a recording, it will always be at 60 Hertz (Okay, there are exceptions, but by 1950, as long as you were on the electrical grid, any hum you experienced would be at 60 Hz). So once I had that reference point, I used a hum removal tool on the original and found the hum went away when I set it to 62 Hz. This confirmed that the recording was being played back too fast. On the new transfer the hum disappeared when I set it to 60 Hz.

I should probably talk a little about record noise here, as the removal of it is the next step in my process. There are generally two types of noise to deal with. Intermittent, and broadband noise.

Intermittent noises are pops, clicks and crackles which can be removed very effectively. On the other hand, broadband noise is a steady hiss, and is not so easily removed. Whenever I do a record transfer this distinction is always in my mind; I choose a needle that reduces the hiss as much as possible, even if the crackle increases.

My collection of truncated styli

Digital noise reduction tools are awesome, and what they are capable of is amazing. Ultimately though it's preferable to make life easy for the de-noisers. They work best when used lightly. This is why I had a good feeling that I could improve on the original transfer. There's nothing else in the digitization and restoration process of a grooved disc that will affect the final sound as much as the stylus and no amount of digital restoration can compensate for a poor needle choice.

So what are these fancy needles I use? They're called truncated styli. They're basically needles with a little bit of the tip cut off. This is important because over time the more a record is played the more it's likely that damage will occur at the very bottom of the record groove. That's also where dust and debris accumulate over the years. More damage = more noise; broadband noise. Using a truncated stylus allows a record to be played while avoiding all that junk at the bottom of the groove.

Playing one of the original records with a 1.7 truncated elliptical stylus

Sounds simple, right? But with the improved sound comes a different problem. Sometimes when you find just the right needle, it has trouble physically staying in the record groove when it passes something it doesn't like. It skips. When this happens you have to manually pick up the tonearm and repeatedly play the skipping section, applying just the right amount of pressure and get it to sort of play through the skip. Like this:

The lyric is "If I get my head beat black and blue" from the song Mind Your Own Business. I need to have all those words digitized so I can stitch them back together in the computer. The word "blue" was the hardest to catch. I finally got it to play near the end...along with a big thump sound, but that's okay, I can deal with that later. The important thing is that I captured all of Hank's words. I should note that this sample is an edited version of the two and a half minutes it took me to get this section to play.

Now all I had to do was combine all of that into a seamless song! A while later I ended up with this:

That's much better. The next step was to use some of my digital noise reduction tools to minimize the surface noise. After a few adjustments:

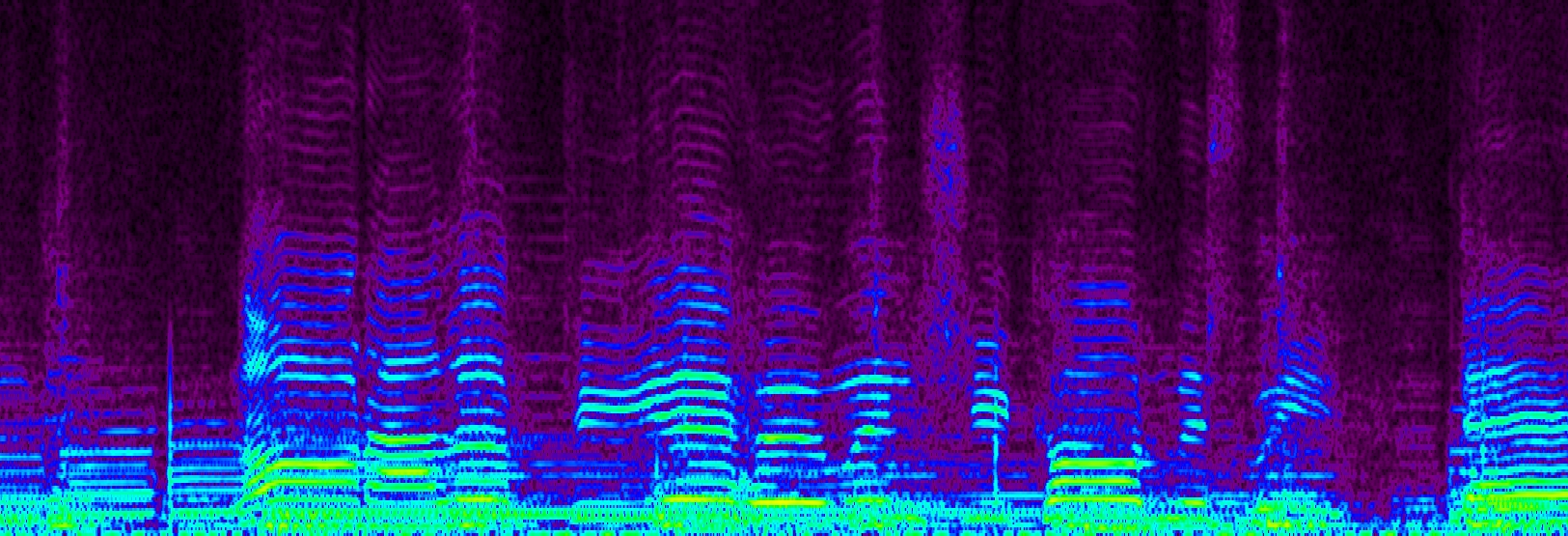

Better still, yes? However, that thump was still there on the word "blue" and there were a few clicks that the de-click tools missed so I needed to deal with that. How? Only one way I know of: manually remove anything that sounds wrong using a spectrum editor.

Spectrum editor view of Hank Williams audio file

Spectrogram editing is a whole other blog post, but let's just say it's sort of like copying and pasting good parts to bad parts with a little bit of Photoshop mixed in. This is super granular level audio editing and it's super time consuming, but the results can be amazing. This is the part where I really feel like I'm rescuing a sound recording from oblivion and making it accessible to a listener. Hank Williams deserves nothing less.

How much is too much restoration? My basic rule is if the fix to a problem changes the original sound in a negative way, live with the problem. Sometimes a digital restoration tool can remove or minimize an offending sound but it will leave a new offending sound in its place. These are called artifacts. In my opinion, they're often much worse than the original problem in that they sound really out of place and draw your attention to the "fix" more that the original issue. It's the stuff that gives audio restoration a bad name. There's a fair amount of hiss that I decided to leave in the final recording because as soon as I reduced it the sound quality changed in a bad way. It took it from a nice, lively analog sound to something digital and altogether wrong. I'm willing to live with the hiss.

Full circle. The new, gorgeous Omnivore LP enjoying a spin on the same turntable on which I transferred the original 16" transcription discs.