By Michael Graves

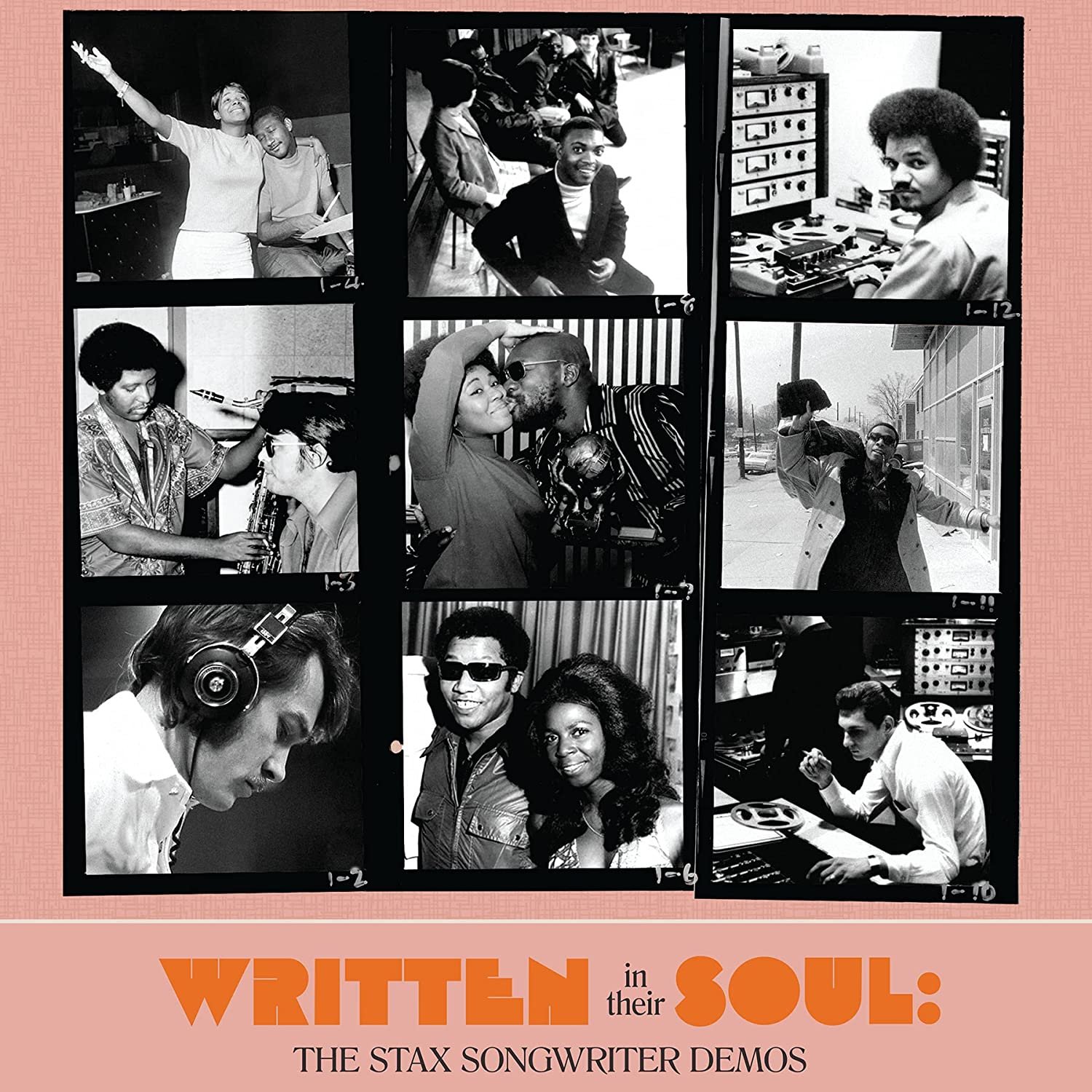

On June 23, 2023, Craft Recordings released Written In Their Soul: The Stax Songwriter Demos. There are two stories within this monumental release; the first is the story of the Stax songwriters and performers, and the music they made. It’s the entire reason for this project. The second is the story of how this project came to be. There’s been so much great, insightful writing on the first story (Rolling Stone, Memphis Flyer, KCRW, New Yorker Magazine, Goldmine Magazine), not to mention Deanie Parker and Robert Gordan’s excellent album notes in the boxed set itself. But I wanted to shed a little light on my part of the second story, specifically the audio restoration and mastering side of things.

Some background

(L-R) Cheryl Pawelski and Michael Graves at The Stax Museum of American Soul Music - Memphis, 2017 (photo Pat Rainer)

The driving force behind Written In Their Soul is Cheryl Pawelski, who has been working on this project since 2006. I started working with Cheryl in 2013 on the GRAMMY-winning Hank Williams album, The Garden Spot Programs, 1950 (more about that here). After that collaboration I think we both realized we were a good fit. A person who does the sort of restoration and mastering work that I do is only as good as the projects I’m given to work on. Cheryl has a never-ending stream of projects with challenged audio, and these live or die on whether that audio can be made listenable.

The original analog tape recordings presented in Written In Their Soul were never meant to be released as records. They were demo tapes made by the Stax songwriters who hoped their songs would be recorded and released by the big stars of the day. The recordings themselves (from the 1960s and 1970s) were generally fantastic, mostly because everyone involved in making a recording at Stax was at the top of their game. After the demo tapes served their purpose however, there wasn’t much need for them anymore and they ended up at East Memphis Publishing, the publishing arm of Stax, and were forgotten.

During the late 1980’s, the original analog recordings (most likely ¼” open reel tape and a few cassette tapes) were transferred to DATs (Digital Audio Tape) and the original tapes were thrown away. This wasn’t uncommon. In the early days of digital recording DATs were used to “preserve” older analog recordings because they were small and thus, space savers. Then in the early 2000’s, as it became clear that the shelf life of a DAT was not as long as everyone had hoped, the DATs at East Memphis Publishing were migrated to hard drives to mitigate any further quality loss.

These hard drives are what Cheryl Pawelski was given to work with. After she made copies of the music and what information existed, she started the herculean task of sorting through all that stuff. Thousands of hours of audio, randomly recorded to DAT, some of it Stax and some of it non-Stax. It took her over 17 years to pull all the useable music she thought were original Stax demos to one side. In the end, she had over 650 tracks.

This is where I come in.

Once Cheryl had decided on the songs that she wanted to focus on for a potential boxed set, she asked me to start cleaning them up.

I’ve been restoring and mastering/re-mastering audio since 1998 and I feel like everything I’ve worked on so far in my career has prepared me for this project. Every problem imaginable was present here. It was a “Greatest Hits” of noise issues; distortion, left and right EQ imbalance, intermittent left and right volume imbalance, azimuth issues, dropouts, missing chunks of audio, static, buzz, speed fluctuations, squeals, extreme hiss and broadband noise, digital rot, garbled tape, moldy tape, mud encrusted tape - name your favorite sonic affliction and it was represented here.

Remember that the DAT format during the time of the original transfers was limited to 44.1 kHz, 16-bit PCM digital audio, so that was what I had to work with. Consequently, the issue that was most present across all the files was the thin, digital sound of those early DATs. If you’re familiar at all with the “Stax Sound”, it should be anything but that. Here’s Bobby Manual on the subject:

Initial restoration and mastering

“Stay With Me”

Written by Eddie Floyd and Steve Cropper

Vocals - Eddie Floyd

Eddie Floyd (Bill Carrier Jr. photo Courtesy of the Concord API Stax Collection)

This is the original DAT transfer of Eddie Floyd singing “Stay With Me.” There are a few things to notice here; first, there’s an EQ imbalance where the upper frequencies are more present on the left which causes the song to lean a little bit in that direction. Also, this file is out of azimuth, meaning the left and right sides are slightly out of sync. This can give a slight stereo sound and that spaciousness can almost sound pleasing, but at the cost of making the overall sound a little limp. And, as previously mentioned, there isn’t much bottom end.

It actually doesn’t sound that bad - this is a good example of how a fantastic song can resonate regardless of the audio quality.

But I knew it could sound better. Here’s the finished version with the EQ and azimuth adjustments - notice how the azimuth correction helps to bring everything into focus and make the whole recording tighter and more impactful, while the new low end gives the whole song a solid foundation.

Deep dive 1: Upside-down tape

“Either You Love Me Or Leave Me”

Written by Homer Banks and Carl Hampton

Vocals - Homer Banks

(L-R) Homer Banks and Carl Hampton. (photo Courtesy of Rose Banks/Homer Banks-Stax Photo Collection)

I wasn’t there when the original tapes were transferred to DAT, so I’m only guessing here, but I assume someone was given a stack of tapes, a reel-to-reel deck, and a DAT recorder and told to get busy. Tape expertise may not have been a top priority. I don’t mean to sound harsh toward whoever made these transfers though. If not for this early preservation effort, we may not be talking about this music at all. But, for whatever the reason a few of these tapes had gotten flipped over and were played back from the wrong side as they were being transferred.

What does that mean? Audio tape has iron oxide on the top surface; this is where the sound is recorded. The other side of the tape is the backing; it’s what holds the recording part together. Normally when you play a tape, the iron oxide surface flows across the playback head and the recorded sound is reproduced. But unless you have some knowledge of audio tape it can be hard to distinguish the top from the bottom of the tape. I can easily understand how someone might thread the reel incorrectly and think everything is okay. If you play a tape on the wrong side, with the backing against the playback head, sound is reproduced but it’s like there’s a pillow over the top of a speaker – very muffled…all low end and no high end. Like this:

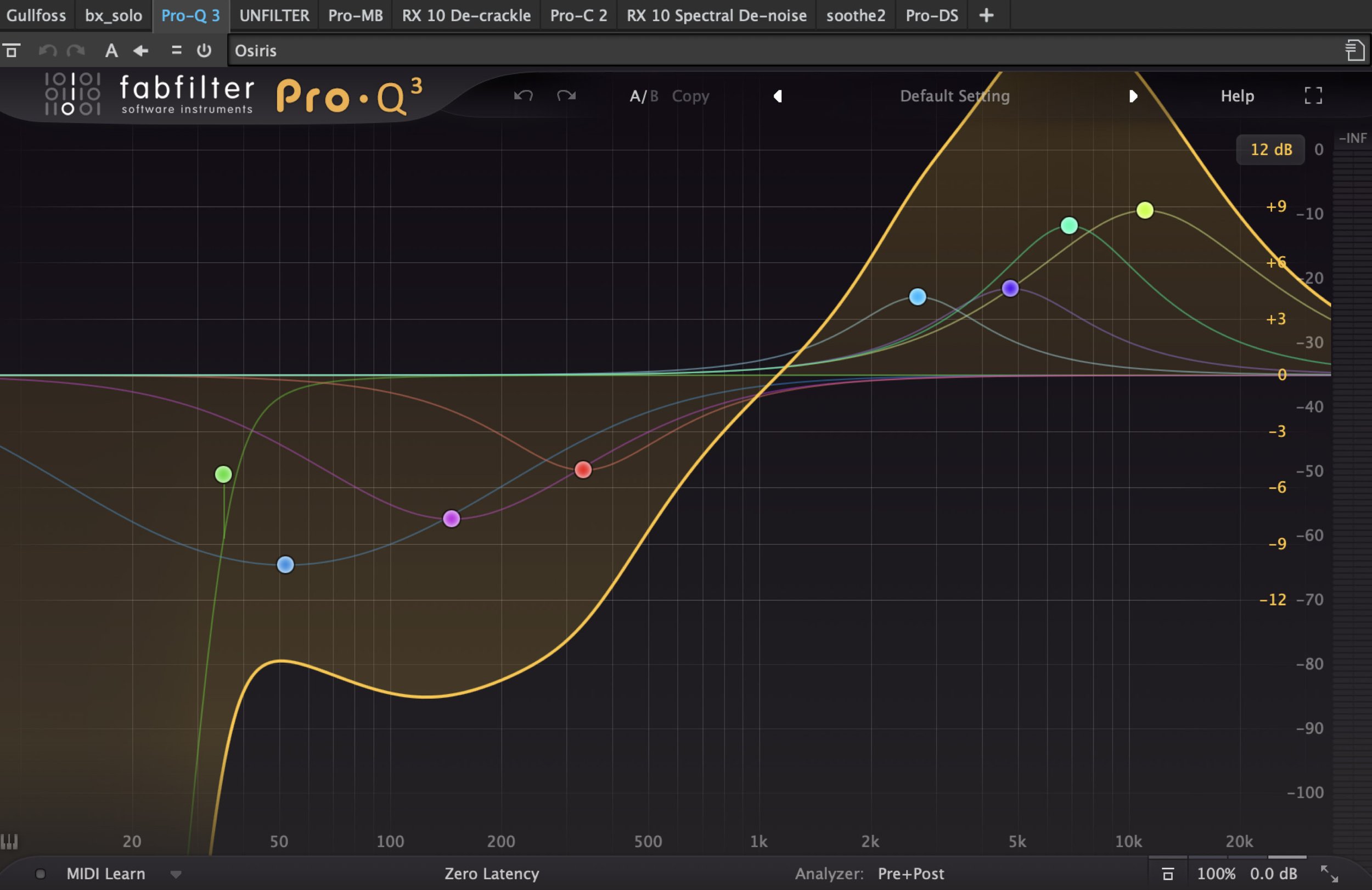

What do you do with that? Get an EQ and start digging around in the spectrum to see if there’s anything there that can be boosted or cut to try to even out the tone of the song.

For those unfamiliar with an equalizer (EQ), the left-hand side of the graph represents the low, or bass sounds and the right-hand side of the graph represents the upper, or treble sounds. I made changes here that are way past the comfort level of most mastering engineers. We typically work with incremental EQ changes, maybe 1-3 dBs of adjusting. In this case I raised the top end over 30 dBs and cut a similar amount on the low end.

The EQ is only part of the story. There’s a thing that happens when you do this kind of work where when you fix one problem, you uncover ten more problems. So, there were a few more processes that happened after the EQ to help maintain the good stuff it was doing while minimizing the bad stuff it brought up.

After all that, the recording actually sounded quite nice.

A Way deeper dive, Part 1

If you really want to know - after the EQ I added a great tool by Zynaptiq called UNFILTER, which helps to reduce comb-filtering. It also added some clarity. Next was Fabfilter’s Pro-MB multi-band compressor to address the dynamics of certain frequencies. After that I used iZotope RX’s De-crackle, because that much of a boost to the top end invariably brought out some static, hash and other crud. Then I used Fabfilter’s Pro-C full spectrum compressor, because when you do this much sonic manipulation the overall dynamic range can become exaggerated. Following that was iZotope RX’s Spectral De-noise. Again, that huge amount of top end that I added came with a cost and that cost was an enormous amount of hiss and other broadband noises. Next up was Oeksound’s Soothe 2, because why not? At this point I would try anything to wrangle this audio. Soothe 2 is an intelligent harshness reduction tool. Seemed like a good idea, and it made an improvement so I kept it in the chain. Finally, I ended with Fabfilter’s Pro-DS de-esser because if you go back to the iZotope de-noise, I had to hit it pretty hard. Anytime you do heavy FFT processing, exaggerated sibilant sounds are almost always a by-product.

The only thing that still bothered me was some distortion on Homer Bank’s vocals, especially when he sings with a little more emphasis as on the word “beg” in the first lyric, “Why should I beg you to love me?” I was very happy with everything else, but the vocals kept nagging at me. The problem was that all I had was one mono file and anything I did to try to target Bank’s voice would negatively affect the rest of the recording. If only I had access to his vocal track by itself.

This was around 2019 and at that time, de-mixing was starting to become a viable option. De-mixing is where you take a recording, feed it through a processor, and hopefully end up with individual files for all of the elements of the recording; essentially generating multi-tracks from a mixed recording. The technology was fairly new at that point but I had used it on a Janis Joplin project a few months earlier with excellent results so I thought I’d give it a try. My favorite de-mixing tool currently is Hit’n’Mix’s RipX DAW PRO. To my ears it’s the most transparent processor of this type so that’s what I used here.

I ended up with four tracks (bass, drums, other and vocals) that I then could then open up in my workstation, Wavelab Pro 10. The bottom track that’s highlighted is what I was going for and it turned out great. As you listen to the isolated vocal track, you can hear the distortion or static that I mentioned earlier. For lack of a better word, it sounds hairy to me. It needed a shave.

All of that static lived in the upper frequencies (the ones that I boosted way back at the beginning of this process) about 7 kHz and above. So now that I had the vocal track by itself all I needed to do was use the EQ again and shave off everything above that frequency. There was a little bit of low-end distortion as well and since I had the vocal track isolated, why not cut that junk out too?

A Way deeper dive, part 2

Again, the EQ shaving was not the only story here…a lot happened after that. Following the EQ cut I used another excellent tool made by Zynaptiq called UNCHIRP to address some of the audio artifacts from the de-mixing process.

I want to single out Zynaptiq here and give them some special love because as far as I know they are the only plug-in manufacturer who makes a tool to specifically address MP3 artifacts, such as watery and chirpy sounds associated with poor quality MP3s. Those sounds are similar to artifacts created when you need to be a little more heavy-handed with de-noisers or anything that uses FFT processing. De-mixed audio can also exhibit artifacts such as this. UNCHIRP is not perfect and can require some trial and error to dial in a transparent sound, but it is an essential tool in my bag. My hope is that there will be further advancement and refining in dealing with these sounds. MP3s and FFT processed audio are not going away anytime soon and audio engineers need tools to address issues like this.

After that I used Fabfilter’s Pro-DS again, because anytime you go this extreme with processing, siblants are a problem. Then I used Fabfilter’s Pro-C compressor for the same reasons I mentioned above. At that point I had gone way past my comfort level with the amount of processing I was doing and the vocal track was beginning to sound a little dry and closed off. Most of the natural reverb had become a casualty of everything I’d done so far, so a little bit of added reverb with Fabfilter’s Pro-R helped. Finally, because I was throwing just about every tool I had at this thing to clean it up, it was sounding unnaturally quiet in parts and did not match the time period for this recording, nor did it match the rest of the audio that it was supposed to be mixed with. Time to add some “pleasing” noise - tape hiss, with U-he’s Satin.

Much better! Now all I needed to do was mix the new and improved vocal track back to the rest of the mix.

I’m the first to admit that this song sounds processed, but the alternative would be to leave it off of the project, and this song is just too good not to ever be heard again.

Deep dive 2: tape dropouts

“Something Ain’t Right”

Written by Mack Rice

Vocals - Mack Rice

Before we get into this, you might want to know a little more about Mack Rice. And his guitar.

Tape dropouts are pretty common if you work with historical audio. They can be caused by any number of things, but audio restoration engineers deal with these issues frequently. The following is an extreme version of what they sound like. Dropouts are basically just a momentary decrease in volume in both channels simultaneously or either the left or right independently. It can be particularly distracting when the latter happens because it has a very unpleasing ping pong effect from left to right. So what I need to do is surgically go into those areas and turn them back up, just raise the volume where there is a lack of volume. As you listen and watch the video below you’ll notice darker areas as the sound decreases.

“Something Ain’t Right” viewed through a spectrum editor in Wavelab Pro 11

Fortunately this is not a complicated fix, you just need a lot of patience. This is also where you can put your Photoshop skills into action; my technique is to use a spectrum editor, highlight the darker areas and increase the gain in that section until it looks and sounds normal. When using this technique, if raising the volume doesn’t work the next thing I’ll try is to copy and paste similar sounds from other areas of the recording. (Oh yeah, this was also an upside-down tape transfer so I had to do everything I mentioned in the first example as well.) Here’s the finished version:

I was happy with the results as this recording was one of the more rustic ones. Do I wish it sounded better? Yes, but everyone involved was happy that we could include this song in the release.

Analog Tapes

Up until now, I’ve focused exclusively on the DAT transfers because that’s all I had to work with for two years. However, later in the process some tapes were made available that we knew might contain additional material for this project.

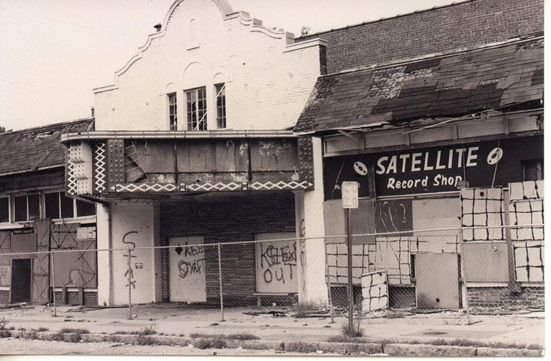

Stax Records went bankrupt in late 1975. The building slowly declined over the years and was eventually torn down in 1989. As word got out that the building was going to be demolished, enterprising Stax enthusiasts in Memphis went to the old building to see what they could find. Robert Gordon (one of the co-producers of this release and co-writer of the liner notes) was one of those people. He and a friend went to the old building. The cyclone fence in the back was broken, much of the back wall and the roof were missing. Gordon found a closet where some cardboard boxes filled with tapes were stashed. They were wet, muddy, covered in salamanders and insects. He made rough transfers over the years and then donated the tapes to the Stax Museum. The Museum itself also had some tapes, and the decision was made to send the whole lot here to Osiris Studio in Los Angeles to be cleaned and transferred.

Now, as you’ve read through all of this so far you may have been thinking, “If only this Graves guy had actual analog tape to work with instead of the DAT transfers.” I know, I was thinking that in real time. However, “going back to the original analog tapes” can sound more romantic than it actually is. Those tapes can also have problems.

The last one was particularly difficult. I can deal with mold, dirt, dead insects, the occasional joint and other fun things that come with the business of working with historical audio tape, but this is the first time I had a tape with cement crusted all around the reel. After physically cleaning the reel and tape as much as possible we needed to get the tape off of the broken reel and spooled onto a new reel in order to play it. More fun.

The image on the left shows us using a reel-to-reel player to simply hold the tape as we slowly try to unwind it, then feed it into a splicing block to put any tape breakage back together. Something sticky had gotten into the tape so it required a fair amount of cajoling to unwind it. The image on the right shows Jordan McLeod, who works here at Osiris Studio restoring and mastering audio, patiently making those splices. This is acetate-based tape and is notoriously prone to breaking under normal circumstances. Imagine how delicate it was given its storage conditions before Robert saved it. Jordan ended up spending some serious quality time with the splicing block on this one.

So, what did this new batch of tapes yield? William Bell’s demo for “Slow Train,” for one. It was hidden away in the tapes that Robert rescued. From the tapes that the Stax Museum held (most likely donated to them by Steve Cropper) we found four Staples Singers rehearsal takes from the Soul Folk in Action album, recorded live in the studio. This ultimately expanded the parameters of the project that Cheryl set for herself regarding the exclusive use of songwriter demos. I’ll let her pick it up from here:

“Every project has a certain code to crack, they’re puzzles in a way, that you can’t really solve, and thus, organize until you have all the elements. Only then does it become clear what a project wants to be and how it needs to be organized to tell its story. You just have to be patient. With this project, I set up some rules for myself which essentially operated as different thresholds and guidelines, like number of discs, number of tracks by any given artist/writer, etc. Once we had the four Staples rehearsal tracks, I just threw all the rules out. It was so important to have the Staple Singers represented because of their success with the label and all the amazing songs they cut - those that were hits and those that weren’t - it was just such a fruitful time for the group. There were no demos by the Staples because they were mostly cutting other peoples’ songs, so they weren’t demo-ing tracks for other artists to cut, they were the recipients of demos by songwriters who hoped The Staple Singers would record their song. These rehearsal tracks then, were the step in between the demos they received and the album recordings they made, so close enough! I was also afraid the tracks would be orphaned and never released if we didn’t include them and they are great, so they turned out to be the perfect way to represent The Staple Singers in the project. Once I relaxed the rules for these tracks, I had to expand the package, so this decision opened up room to include more songs. We were even able to include two different versions of songs in a few instances, which was great and informative.”

Here's a good example for that last part. Unbeknownst to me at the time, we had two versions of the song, “Too Much Sugar For A Dime”, written by Homer Banks and Raymond Jackson; an early demo where Banks sings and a later, more fleshed out version with Bettye Crutcher singing. Cheryl asked me to restore and master the song. I’m sure she specified the Bettye Crutcher version, but somehow I missed that and pulled the Homer Banks version, did my thing and sent it to her. After we both realized what had happened and confirmed that the two versions were equally awesome, we decided that everyone needed to hear the pair of them. With the guard rails recently relaxed, Cheryl included them both on the release and the world is a better place for it.

(L-R) Raymond Jackson, Bettye Crutcher, Homer Banks (photo Courtesy Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

"Too Much Sugar For A Dime"

Written by Homer Banks and Raymond Jackson

It was incredible to work with this extraordinary material. I think I can speak for Cheryl and myself and say that the legacy of Stax is so strong, vibrant and deeply meaningful, that to have been able to contribute it in any way has been our honor.

Stax Museum - Memphis, 2023 (photo Michael Graves)